Paint and plaster analysis results and an assessment of the historic paint schemes used in the Painted Chamber at Kirkby Hall

Introduction

The Kirkby History Group asked M Womersleys to undertake limited plaster and paint analysis to help them further understand the upper painted chamber at Kirkby Old Hall. This short report provides this analysis with additional paint samples and other information that may be useful to the group.

Summary

The pigments used to produce the paintings suggest they were created in the 15th or early 16th century, within an upper chamber of a former timber-framed solar wing to an earlier smaller-scaled building. The plaster analysis and the lack of setting out with red pigment in the upper frieze band suggest that the painted walls and frieze may have been applied at different periods but perhaps still within 50 years of each other.

Putting the paint and mortar analysis within the context of the building

Whilst the first-floor space in which the painted murals sit is referred to as a chapel, it is more likely to have been the solar wing of an earlier house that has been rebuilt against it. The wing is roofed with a crown post roof. The listed building description suggests that the East wing dates to c1450, and the hall and the west wing c1530. However, whilst the west wing may have been encased in stone in c1530, it was a timber-framed wing to an earlier house with a gable to the front, facing down the avenue, as a 1914 description sets out (the present hipped roof, the west slope of which is continued straight up till it joins the main roof above the hall, being quite modern).(Farrer 1914) The upper floor is unlikely to have been designed or decorated as a chapel, as suggested by the building's historical descriptions and the listed building description; rather, it is a decorated upper chamber for the principal members of an early 16th-century household.

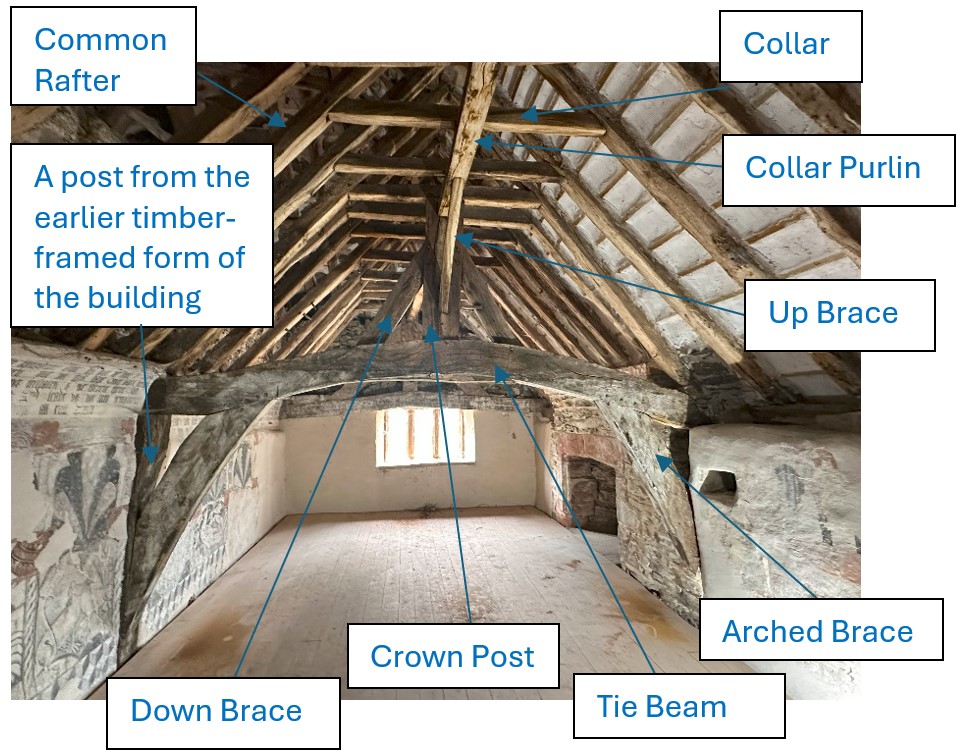

The upper painted chamber in the list description is also incorrectly described as having an open kingpost roof with arch braces and struts. It has a double-rafter crown post roof, with short posts rising from the tie beams, carrying horizontal purlins that support the collars of each set of rafters. The collar purlins are braced back to the crown post, and struts rise from the crown post to the collar purlin. These spaces in single-rafter roofs were often finished with a segmented barrel-vaulted structure, but the painted chamber, in common with other double-rafter roofs, (J. Brunskill 2000, 78), appears to have previously had a ceiling with decorated exposed tie beams or arched braces. These roofs in the north of England usually date from the 13th century. They were the dominant roof form in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with some still being constructed in the first half of the 16th century. (Meeson 2012) In West Yorkshire, the crown-post roof was often used over the solar until the middle of the 15th century, and in York, it was the most common form of roof structure in the 14th and 15th centuries. (RCHM, WYMCC 1986, 20–21)

The crown-post roof has well-documented use in the north of England. But Cumbria is known principally for its early and continued use of Cruck construction. The survival of an earlier roof and the remnants of a timber frame construction in Kirkby Old Hall is rare in this part of the country, with only a few examples found in Cumbrian towns. (R. W. Brunskill 2002, 151-152) The plaster carrying the painted murals in the upper chamber has been applied onto later stone infill which may have been built when the main hall was rebuilt in stone in the 16th century.

Figures 1 & 2. The upper painted chamber, photograph facing northeast.

Figures 3. Showing the upper painted chamber, a photograph facing southwest

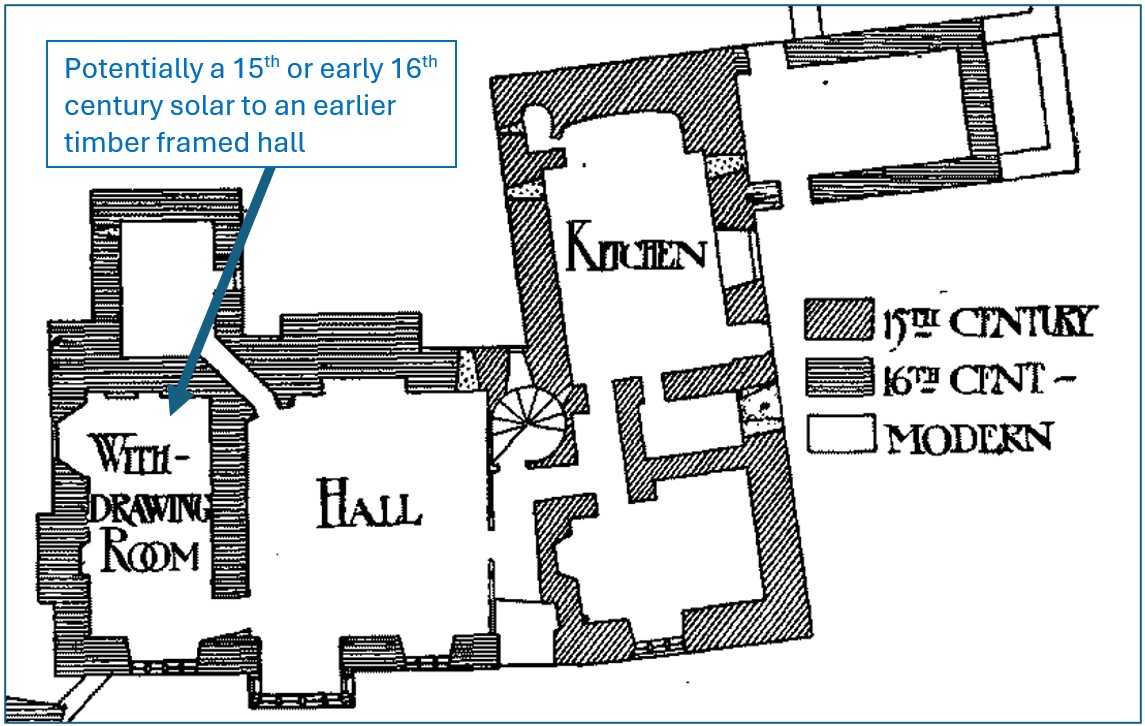

Figures 4. Showing the apparent remains of a mid-16th century dovecot on the outside face of the northeast wall, perhaps not a priest's vestibule as suggested (Ayre 1894, 41), within a later rear extension.  Figure 5. The previously suggested phased development of Kirkby Hall.(Farrer 1914) , repeated in the list description. The withdrawing room and the painted chamber above are likely to have been altered in the mid-16th century. Still, they are much more likely to have been one of the earliest parts of the house and formed a timber framed solar wing to an earlier smaller-scale hall, perhaps open to the roof, to the west.

Figure 5. The previously suggested phased development of Kirkby Hall.(Farrer 1914) , repeated in the list description. The withdrawing room and the painted chamber above are likely to have been altered in the mid-16th century. Still, they are much more likely to have been one of the earliest parts of the house and formed a timber framed solar wing to an earlier smaller-scale hall, perhaps open to the roof, to the west.

The drawing in Figure 6 shows the likely plan form of Kirby Hall by the 17th century (Farrer 1914), which appears to follow the pattern of larger houses built in the lake district in the 16th and early 17th centuries, which saw the abandonment of designs based upon a principal hall open to the roof and changes in the design of the typical ‘H’ plan house. The central block with cross wings was preserved, but the hall became a single-storey room, with a cross wing on one side housing a parlour and dining room and the other cross wing comprised of a kitchen, scullery and other service rooms, rather than detached buildings. The bedrooms above the ground floor correspond with the rooms below. Access to the upper floors was usually via a stone spiral stair.(R. W. Brunskill 1978, 39)

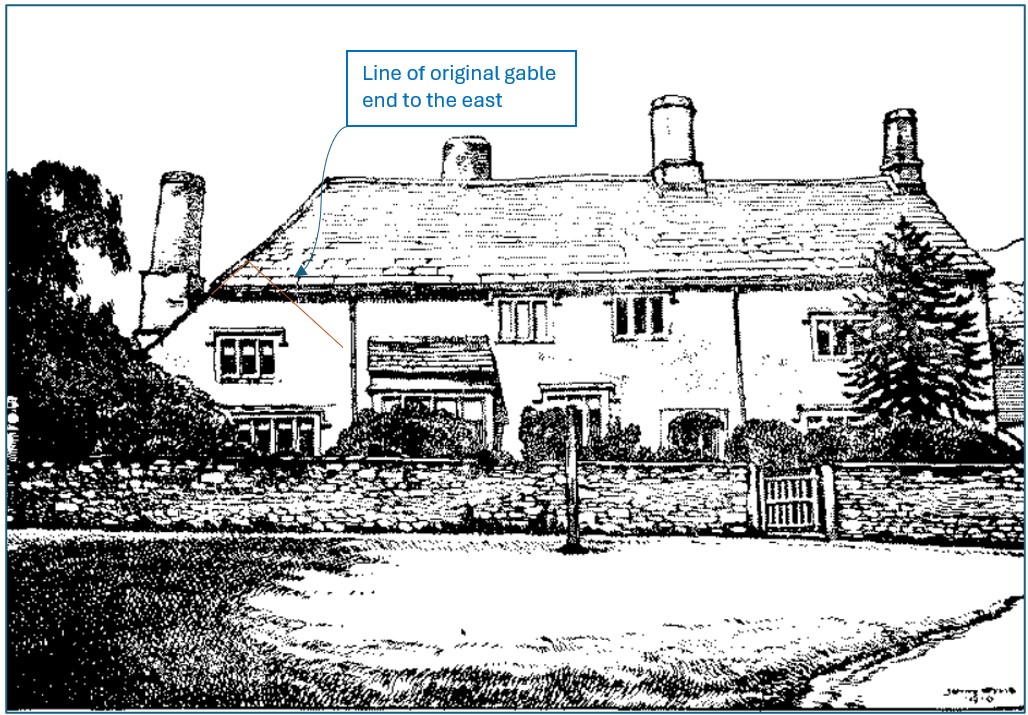

Likely, the upper painted chamber within a 15th-century timber-framed solar wing was absorbed into a later 16-17th century house, with its former southwest-facing timber-framed gable end encased in stone and partly lost within the hipped roof of a rebuilt large adjacent two-storied hall. The original gable end line is shown in Figure 6, which also illustrates how much larger the scale of the building became, with the solar wing no longer being a dominant feature of the building.

The painted mural decoration could conceivably date from the late 15th or early 16th century and be part of a richly decorated, potentially unheated upper chamber. A painted decorative scheme likely covered a ceiling at tie-beam level and the structural elements of an earlier 15th-century timber frame (which previously formed the skeleton of a solar wing at the upper end of an earlier contemporary open hall).

Figure 6. Hand drawing from before 1914.(Farrer 1914) The line of the original gable end, noted in the 1914 publication, illustrates how what may have been a prominent solar wing is now dominated and subsumed within the southwest front. It is much smaller than the later enlarged main hall and house.

Some comments on the painted murals

The murals have previously been interpreted, and the Kirby History Group is employing a specialist to look again at the iconography and decorative details. It has been noted that around the top of the paintings, there is a frieze of quotations from the Lord's Prayer and passages from the Bible of 1535 (or 1541 (Farrer 1914)). The birds have been described as not native to this country, the trees as palms, the framing pillars strongly resembling Saracen piers, and the capitals as reminiscent of Eastern metalwork. Some of the animals, it has been suggested, are from 14th-century Indian artwork or similar to those found in various medieval books of beasts.(BURKETT 1999) However, the imagery of birds and the stylised palm trees do not appear to have directly originated from the different versions of the ‘Books of Beasts’ around the 12th century and beyond, as described by others. (White 1980), (Morrison No date) I would suggest that the inspiration, at least partly, came from other more local artwork created in the mid-16th century. Birds, lions' heads, plated twisting columns, bulbous capitals, and decorated vase bases on columns are all seen in wooden overmantels at the nearby Sizergh Castle.

The decoration does not seem to mimic tapestry hangings as is thought to be the case at Gainsborough Old Hall in the late 16th century, (Babington, C. Manning, T & Stewart, S. 1999, 61) or as at the newly discovered early wall paintings at Calverley Old Hall. They appear to be fashionable decorations applied directly to walls in the early to mid-16th century to a fine chamber within a solar wing of a former timber-framed house. Interestingly, the decorative band at the base of the paintings is similar to the lowest tier of paintings at the Great Hall in Belsay Castle, in the northeast, from the 15th century, which retains faint traces of a three-dimensional chevron pattern. (Babington, C. Manning, T & Stewart, S. 1999, 70)

The idea that this space was decorated as a chapel is hard to comprehend. The framing below cusped arched openings is one of the few suggestions of religious art. Still, it could have been used to give the murals' setting finesse and pedigree, and religious texts are seen in other painted rooms that were not used as chapels. There are no images of the ‘Wheel of Fortune’, Martyrs, Devotion to Mary, St. Christopher or St George, ‘The Harrowing of Hell’, or even simple red and black tear decorations representing Christ's tears and sweat when he was crucified. These images have been well documented in late medieval churches and chapels. (Rosewell 2011)

The plaster background to the painted murals

The murals are painted on lime-rich, hair-reinforced plaster. The plaster was used to even out the rubble stone walls' background and provide uniform grounds below the painted murals. The painted structural timbers in this room may have been painted without any special preparation or primed with a simple coat of size or oil paint. (Thompson 1956, 41) Two plaster samples were analysed; it is thought that one is from the upper sloping frieze area and the other is from the wall, although both samples were taken from previously fallen plaster. The results are set out in Appendix 3. Sample B contained coarser aggregate and less hair and appeared like a solid wall lime plaster. Sample A contained more significant quantities of lime and hair and may originate from the hardwood lathwork (that will date to before the mid-16th century when it was superseded with more available faster-growing pines), which provides a background to the sloping frieze. The thin section photographs done as part of the paint analysis in appendices 1 and 2 appear to show that Sample A did not have a finer finish plaster applied over the top of the undercoats and, therefore, needed to be able to be worked smoother in fewer coats and required a rich lime mix which would also need additional hair not only to form nibs over the laths but to reduce shrinkage in it. Sample B appears to be similar to the undercoats shown in the cross-sectional photos in Appendix 1, which have a finer-grained lime fine stuff plaster applied as a finish coat. Both plasterers are sufficiently different to suggest they may have been applied in separate phases. The addition of Plaster of Paris suggests that at the same time, this plaster was applied, other ornamental work may have been produced elsewhere in the same house during the same period. However, it should be noted that Gypsum deposits are to be found within Cumbria and may have been commonly used to speed up work and counter shrinkage in lime plasters.

The pigments and techniques that appear to have been used to create the painted murals

The murals appear to utilise red oxides (oxides and oxyhydroxides of iron have been essential sources of pigments from the Middle Ages onwards, (Thompson 1956, 75), (Howard 2003, 141) ) and a form of carbon blacks, either charcoal or coal ash (The monks of St Bees Priory granted permission for coal to be dug around Whitehaven as early as the 13th century, and the images taken in the UV-visible spectrum show no absorption of this light which can suggest coal ash powder). The use of these pigments indicates that the murals are likely to date shortly after the rebuilding of the walls of the painted chamber with stone, as a much more comprehensive range was more readily available by the mid—17th century.(Bristow 1996) These colours appear bound by an oil-binding medium, which naturally modifies the optical nature of the pigments used. This binder tempers them. Oils from the mediaeval period onwards included linseed, hempseed, and walnut oil, some concentrated by drying in the sun or boiling.(Thompson 1956, 67) Adding the pigments to limewash could not have produced the red and black colours, as the formation of calcium carbonate as the paint cured would have considerably dulled them down. These same dark limewashes cannot be used to portray details with consistent accuracy in painted murals. The reds and blacks have visible particles, as they exhibit colour to their best effect if the crystals and particles are not too fine. If bone black or flame black from coal soot had been used, both used from the medieval period, (Rosewell 2011, 136) the pigment fragments would not be visible.

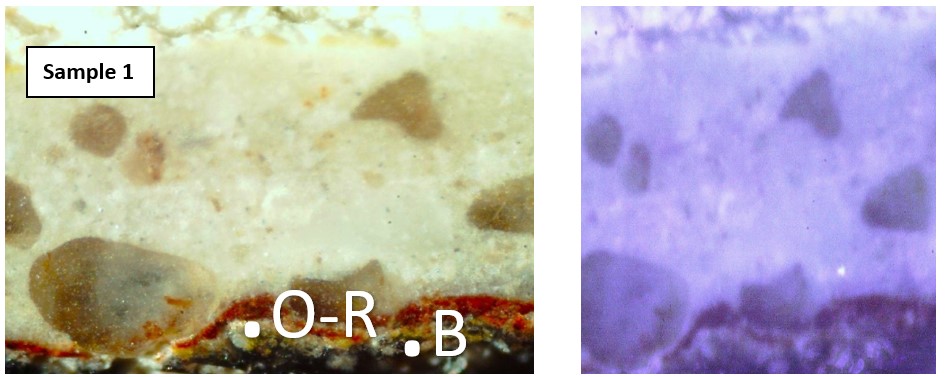

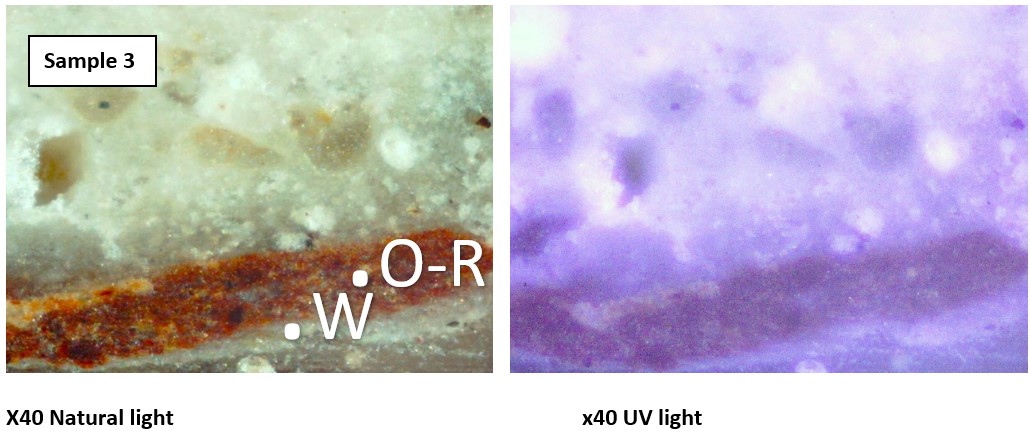

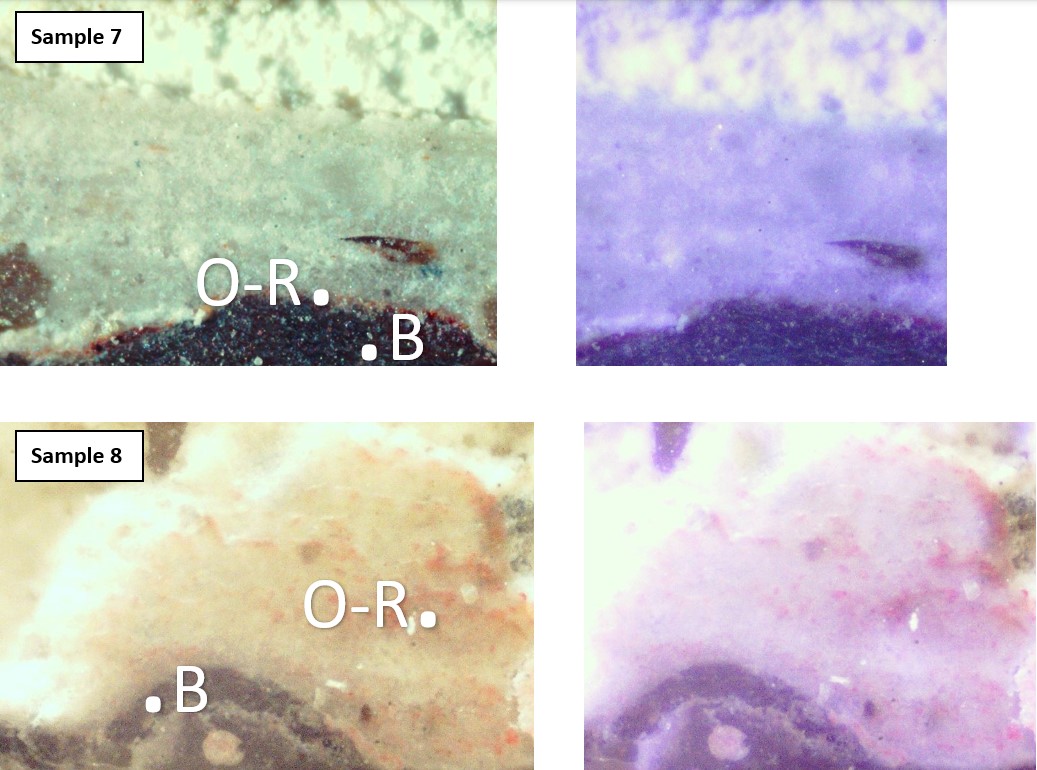

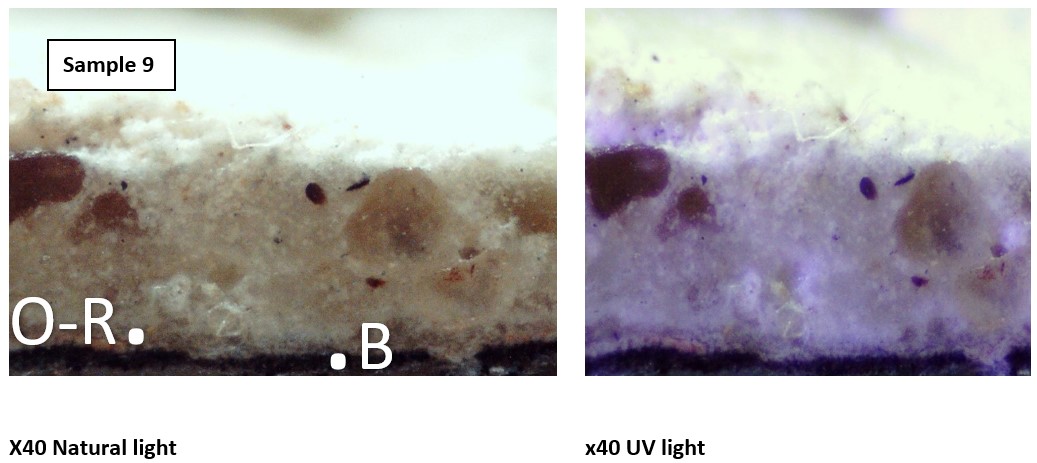

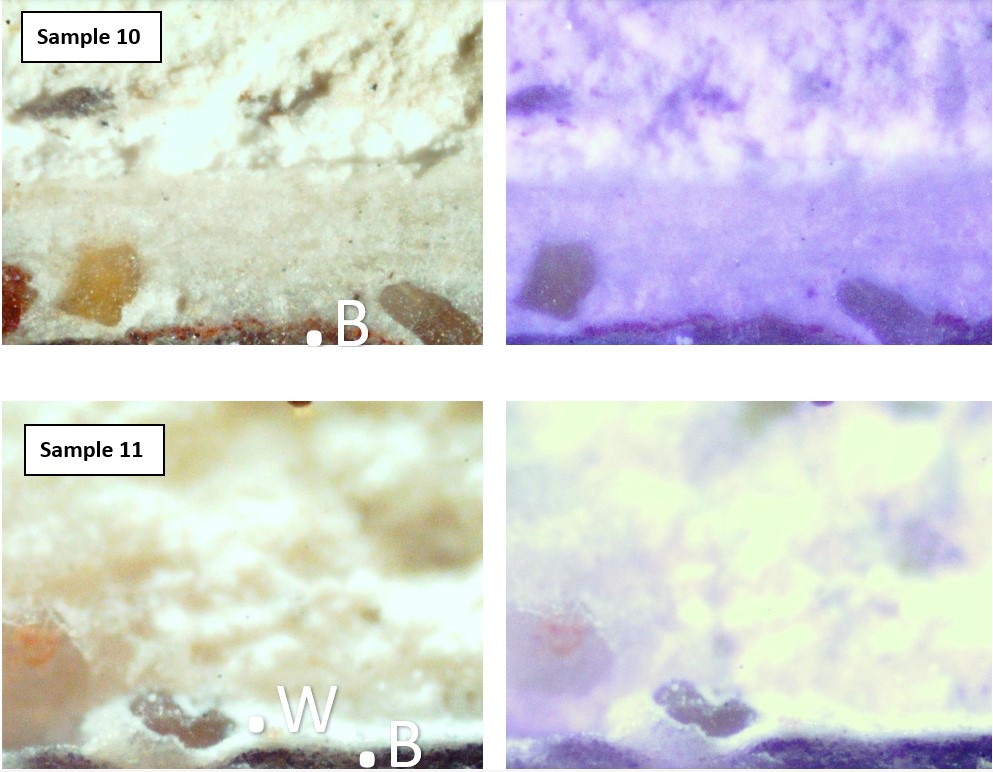

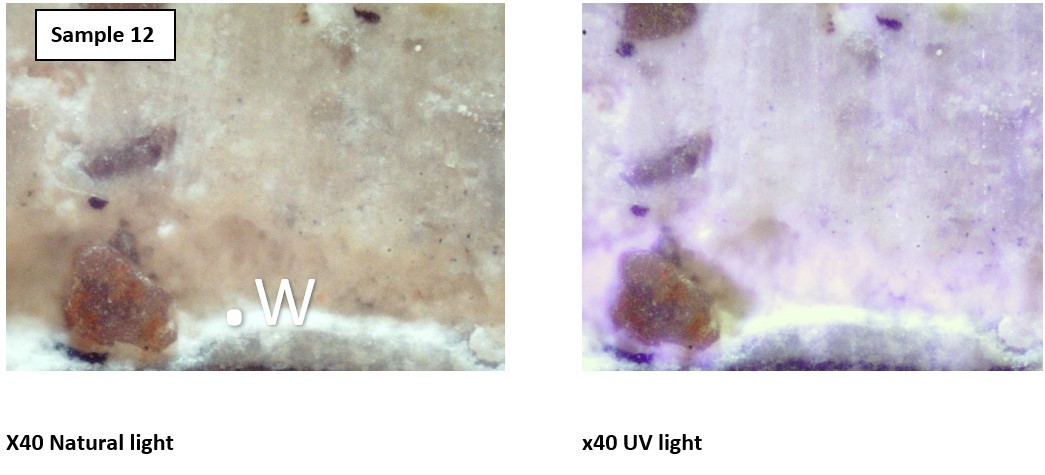

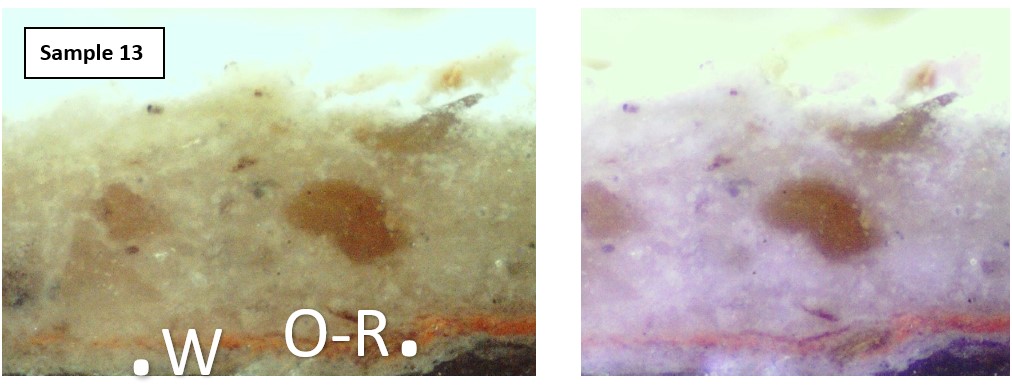

The white detailing visible on the surface of the paintings may be ‘lime paint’ consisting of burnt, slaked, dried, and ground lime tempered with size or egg yolk, as oils would reduce its opacity. However, the smooth white layer below the surface of the letters in the murals and below the red outline in the pictures is likely to be animal-size bound slaked and ground burnt lime; please see images of samples 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12 & 13.

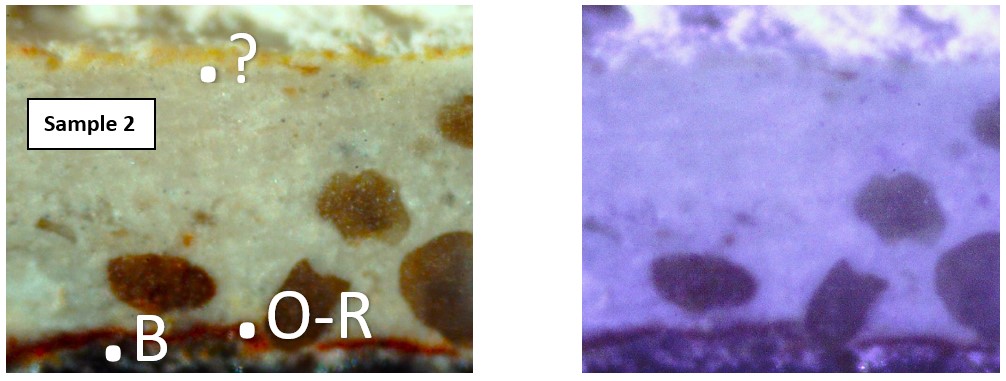

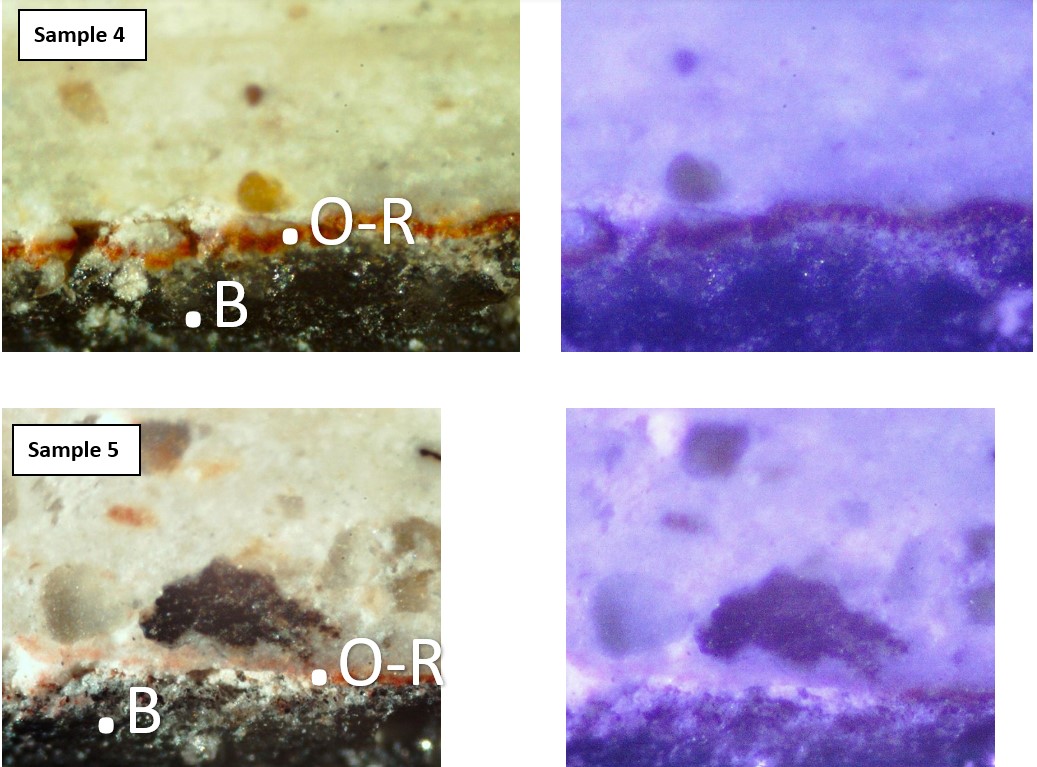

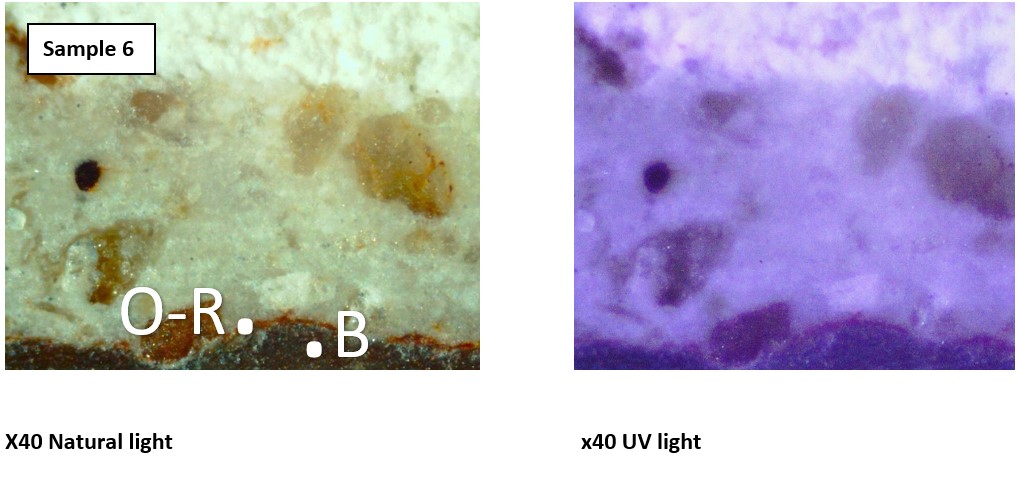

The main body of the murals was applied as Secco painting, that is, painted with pigments in binders onto dry plaster. This represents the norm of English wall paintings being applied onto dry plaster. (Babington, C. Manning, T & Stewart, S. 1999, 17) However, evidence in images of samples 5, 8, and 9 shows a faint red outline within the depth of the lime plaster topcoat. The whole artwork may have been set out by painting red oxide pigment in water onto wet plaster as fresco work, a recognised practice. (Babington, C. Manning, T & Stewart, S. 1999, 17) The use of a red underdrawing, perhaps outlining in more detail the images that were to be painted, also shows up as bound red oxide paint, presumably applied onto ‘sized‘ plaster, as seen in the images shown below of samples 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9 and 10. The red ferric oxide was often used for preparatory sketches (Howard 2003, 143) and in under-paints in medieval church wall paintings. (Rosewell 2011, 137), (Howard 2003, 147) It should be noted that organic binding materials are very difficult to determine without complicated material analysis, and even then, they can deteriorate to a point where they are virtually undetectable. (Babington, C. Manning, T & Stewart, S. 1999, 19)

The paint build-up shows no pigment mixtures, except perhaps lightened back to a blue/grey, which was relatively common in the Elizabethan era. Most areas of decoration were applied in layers of single pigment, and modelling was achieved by applying a separate layer of pigment over the first rather than by mixing the two. Meanwhile, the modelling was achieved using lime-white highlights over otherwise dark figures in other areas.(Curteis 1998)

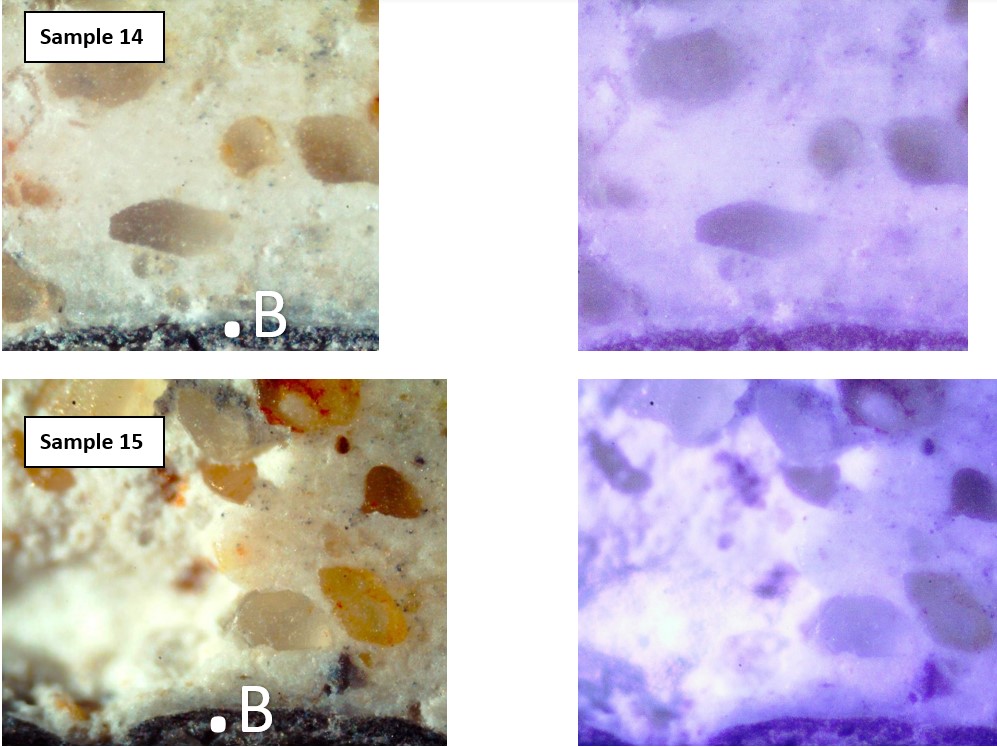

The identity of the painters and their patron are unknown. Still, they seem to belong to two phases, with perhaps no red outline used to set out the texts in the upper sections of the walls. In these areas, the cross sections of the paint and plaster, as shown in samples 14 & 15, show less depth of fine lime finish plaster. Similar simpler colour schemes or red, black and white, can be found in late medieval wall paintings where substantial resources were not available to buy expensive pigments, (Rosewell 2011) which can be seen in 15th—16th-century murals on the upper floor at Dacre Hall. These murals appear to have also been set in a framework of spaces subdivided by columns, and later, in the 17th century, Gainsborough Old Hall also used this subdivision device.

Appendix 1: Images showing cross sections through early paint and plaster from samples likely originating from the wall decoration. (Key: B=Black, O-R=Oxide Red, & W=White)

Appendix 2: Images showing cross sections through early paint and plaster, from samples likely originating from pieces of text decorating the coved areas at the top of the walls.

Appendix 3: Summary of the Plaster Analysis

Two plaster samples were inspected and from the nature of the binding matrix of the first mortar sample and information gained from the analysis, the mortar was probably made by volume from sieved slaked lime, including inert over and under burnt lime and waste ash originating from the lime production process. 30% of Paris plaster and significant amounts of fine animal hair were added to the mix before application.

The second sample was probably made by volume from 2 parts sieved and slaked lime, including inert over and under burnt lime, to 1 part shale fragments, fine quartz-based sand, and waste charcoal, originating from the lime production process. Many fine hairs and 15% Paris plaster were added to the mix before application.

Bibliography

Ayre, L.R. 1894. ‘Kirkby Old Hall’. The North Lonsdale Magazine and Furness Miscellany I (3).

Badington, C. Manning, T & Stewart, S. 1999. Our Painted Past: Wall Paintings of English Heritage. London: English Heritage.

Bristow, Ian C. 1996. Interior House-Painting Colours and Technology 1615-1840. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Brunskill, J. 2000. Vernacular Architecture: An Illustrated Handbook. 4th ed. Faber & Faber.

Brunskill, R.W. 1978. Vernacular Architecture of the Lake Counties. 2nd ed. London: Faber & Faber.

———. 2002. Traditional Buildings of Cumbria. Yale University Press.

BURKETT, M. E. 1999. ‘ART. VIII — Cumbrian Wall Paintings’’. Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Transactions (TCWAAS) 99:159–76.

Curteis, Tobit. 1998. ‘The Elizabethan Wall Paintings of Hill Hall: Influences and Techniques’. Studies in Conservation 43 (sup1): 131–35. https://doi.org/10.1179/sic.1998.43.Supplement-1.131.

Farrer, William, ed. 1914. ‘Townships: Kirkby Ireleth’, in A History of the County of Lancaster. Vol. 8. London: J Brownbill. https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/lancs/vol8/pp392-400.

Howard, Helen. 2003. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. London: Archetype Publications Ltd.

Meeson, Bob. 2012. ‘Structural Trends in English Medieval Buildings: New Insights from Dendrochronology’. Vernacular Architecture. The Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Group 43:58–75.

Morrison, Elizabeth, ed. No date. Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum.

Rosewell, Roger. 2011. Medieval Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches. Woodbridge: Boywell Press.

Thompson, Daniel V. 1956. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. Reprint of 1956 book. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

White, T.H. 1980. The Bestiary: A Book of Beasts. New York: Perigee Books.

Niel V. 1956. The Materials and Techniques of Medieval Painting. Reprint of 1956 book. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

White, T.H. 1980. The Bestiary: A Book of Beasts. New York: Perigee Books.

Related Articles

On Sunday, March 16th, why not come for a full introduction to lime plastering and a practical demonstration workshop?

Learn more about traditional clay, lime, and ornamental gypsum plasters and their use internationally…

Proposals to carry out a conservation assessment at Wukro Cherkos, with a full training programme for recent graduates from Mekelle University and government bodies responsible for regional conservation work.

Introduction In response to continued concerns about the condition of one of Tigray’s most well…

Report on the support given by M Womersleys to Jabir Mohamed at Berbera Museum, Berbera, Somaliland, over two weeks from the end of October 2024

Contents …