M Womersleys runs Hot Lime Mortar Courses, and our workshop is designed to provide an introductory guide to preparing and applying

Organisations that seek to control how people maintain old buildings view using hot lime mortars as beneficial in conserving historic structures. However, they must be used with caution and care.

While this is true, it should be noted that hot lime mortars, used hot, tend to expand and then shrink more as they cure compared to other types of lime mortars, and this can cause de-bonding from the substrate. In addition, the high heat generated during mixing and application can lead to rapid hardening that may not create a strong bond with the original mortar behind.

When it comes to repairs in damp environments, using hot lime mortars is often seen as a strategic advantage. These mortars can appear to set more quickly and help mitigate moisture-related problems in the structure. Despite being physically hot and pulling water out of the surrounding damp fabric, they seem to work well. However, it's crucial to understand that once the hot lime mortar has hydrated to calcium hydroxide, its porosity increases and only decreases as it begins to carbonate fully. This can only happen if it can slowly dry out. Therefore, using hot lime mortars in permanently damp conditions will always lead to the mortar not setting and cause failure as the lime leaches out in wet conditions.

If Hot lime mortar is used in a more sheltered location and can dry out sufficiently to fully cure, it will have good vapour permeability and help prevent water from being trapped within walls. Their use is especially important in areas where the masonry requires moisture management. But it should be noted that for the mortar to cure after the initial setting, it needs to carbonate,(Hot lime mortar can begin to set within a few hours due to the hydration of quicklime, which forms calcium hydroxide. However, this initial setting does not equal complete curing and provides no significant carbonation). The carbonation of lime (conversion of calcium hydroxide into calcium carbonate when exposed to CO2) takes considerable time. Typically, for hot lime mortars, the carbonation process can penetrate approximately 1 to 4 millimetres per month under ideal conditions (sufficient humidity, adequate CO2 exposure, and temperature). The material may cure more slowly with deeper mortar joints since the mortar interior may have reduced access to CO2, leading to slower carbonation compared to the surface layers. This means that if you intend to use hot lime mortars, following their initial hydration process, which may take 4 to 6 weeks with finely-graded, pure, modern, quick limes, they will need protection from severe wet weather for another 2 or 3 months.

Failing hot lime mortar in an area of high exposure.

Failing hot lime mortar in an area of high exposure.

It is always essential that the mortar used for repointing is compatible with the original building mortars and the historic fabric. This means that dogmatic guidelines advocating hot lime can lead to severe failures. M Womersleys undertake substantial amounts of mortar analysis of original building mortars, and from the 17th century, we find that as well as fat lime putty bound mortars, feebly hydraulic lime binders were used, from early in the 19th century, it was not unusual for medium strength hydraulic limes and natural types of cement to be used, and from the 1880’s we find the use of no-fines shuttered OPC bound concrete and Ordinary Portland Cement binders used in construction.

Lime-rich mortars made as a hot mix and allowed to slake over a few months or consisting of lime putty-bound mortars can accommodate thermal changes in buildings where movement due to thermal expansion and contraction is a concern. However, they must be protected from lousy weather for the first three months of curing, and ideally, the work should take place in late spring or summer.

Hot lime mortars do not provide enhanced resistance to weathering in regions with harsher climates where exposure to the elements may impact performance over time. In exposed locations, mortars with a hydraulic set need to be used.

Conclusion

Hot lime mortars have a role to play when made hot and after slaking use in conservation work. However, they should be compatible with the mortars used to construct the original fabric of the building and the density of building materials, and they should not be used in exposed areas even after being properly cured.

Where you decide to use them, wet weather can pose significant challenges to hot lime mortars that have not fully carbonated. To mitigate these risks, it’s essential to:

· Protect the mortar from rain and excessive moisture for at least four months during the initial curing phase if you working during autumn and winter.

· Ensure moisture management strategies are in place, keeping the mortar moist but not oversaturated.

· Monitor weather forecasts closely during curing to implement protection measures when unfavourable conditions are anticipated.

M Womersleys runs Hot Lime Mortar Courses, and our workshop is designed to provide an introductory guide to preparing and applying "hot mixed" lime mortars. These mortars are made by slaking quicklime and combining it with sand, natural hydraulic lime binders, and potentially other additives like tallow.

"Hot mixed" mortars have a long-standing history of use in the UK, with visible evidence in traditional buildings and structures throughout the country. However, since the lime revival of the mid-1990s, the field of conservation mortars has largely been dominated by lime putty-bound mortars or "cold" mortars based on natural hydraulic limes (NHLs). While all these types of mortar serve their purpose, there’s been a renewed interest in the production of what are considered more authentic mortar preparations using quicklime and sand. This workshop aims to guide building professionals through the process of specifying "hot mixed" mortars, addressing health and safety implications, materials, preparation, appropriate mixing equipment, and the specific applications for these mortars.

By the end of the course, participants will be able to identify traditionally made "hot mixed" mortars in historic structures and develop the skills necessary to specify these mortars based on authenticity, performance, conditions of exposure, seasonal considerations, the substrate, and the nature of required masonry repairs.

This course targets building contractors—including stonemasons, bricklayers, lime workers, and laborers—as well as specified professionals such as architects, building surveyors, engineers, and heritage professionals involved in historic building repair, reconstruction, and the consolidation of historic structures. It aims to instill confidence in the successful making and use of "hot mixed" mortars.

Additionally, owners of historic buildings may find this course beneficial for planning maintenance, renovation, or conversion projects for traditional structures.

After the course you should have an: Ability to recognize traditionally made "hot mixed" mortars in historic buildings and structures, Understand analysis techniques to effectively match and specify "hot mixed" mortars for repair work,

Develop repair strategies suitable for masonry repair projects using "hot mixed" mortars, be able to create clear and detailed specifications for "hot mixed" mortar, understand the setting characteristics and aftercare required for the successful use of "hot mixed" mortars.

Course Programme

- The course combines theoretical instruction with practical sessions covering: Health and safety

- Historic preparation and use of lime (and other) based mortars.

- Overview of the range and production methods of lime binders available in the UK today.

- Exploration of other mortar components, including sands, aggregates, pozzolans, and additives such as animal fats and milk products.

- Justification for specifying "hot mixed" mortars, addressing issues of authenticity, performance, and workability.

- Identification of potential failure causes, such as slow slaking, slow carbonation, and environmental factors.

- Developing specifications for lime mortar repairs, including mix proportions, mixing equipment, and Building Standards.

- Addressing perceived barriers to specification, including health and safety considerations for storing materials, mixing, and safe use.

- Best practices for producing sound specifications for "hot mixed" mortars.

Related Articles

The steps members of the Waterton’s Wall restoration team, with support from Mark Womersley, have been following to consolidate, conserve and repair this historic wall that represents the successful efforts of Charles Waterton to preserve the wildlife that lived on his estate near Wakefield in West Yorkshire.

1. Fill deep voids behind the wall’s facing stones with deep pointing work. The works involve …

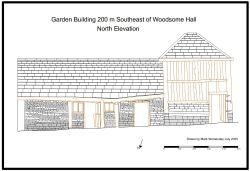

Mark spent a day recording a historic timber-framed garden building at Woodsome Hall

Mark Womersley, as part of his voluntary work with the Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group, spent…

M Womersleys were delighted to offer a day of tutoring to those who attended the Wentworth Woodhouse Working Party

M Womersleys were delighted to offer a day of tutoring to those who attended the Wentworth Woodhouse…