M Womersleys has been repairing the rare late 19th-century, no-fines concrete at Oldham Old Library using hydraulic limes and natural cement binders.

M Womersleys has been repairing the rare late 19th-century, no-fines concrete at Oldham Old Library using hydraulic limes and natural cement binders.

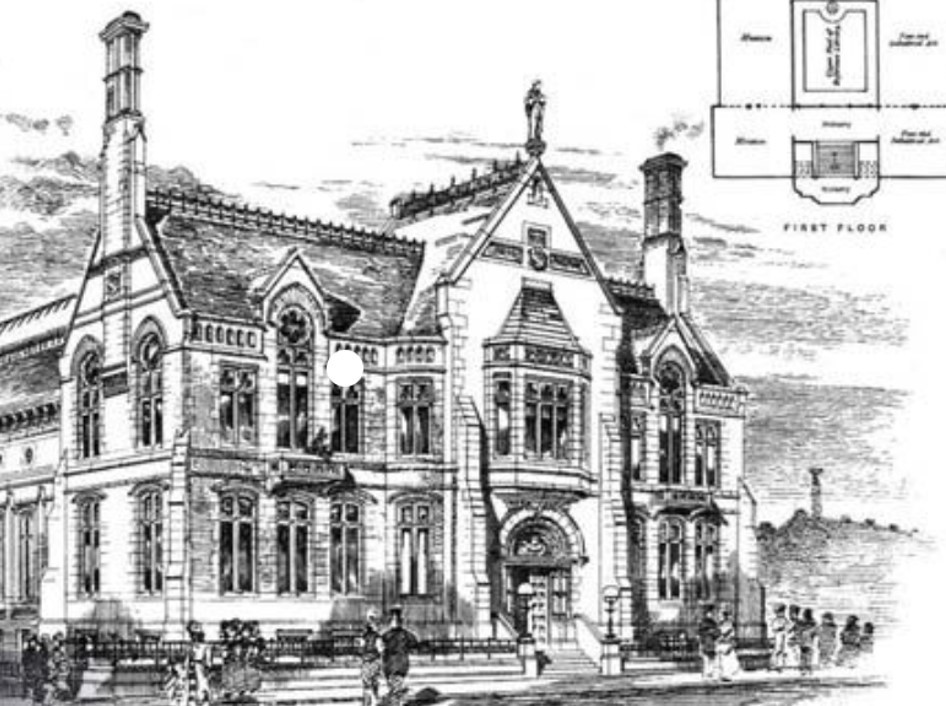

The original Oldham Library and Art Gallery was built in the 19th century and opened in 1883 as a free public library for the community. This followed the broader movement in the UK to establish libraries after the Public Libraries Act of 1850, which allowed local authorities to spend money on libraries.

The building is a very early example of a no-fines shuttered concrete structure clothed in rusticated rubble, coursed and squared into small blocks. It is in the Victorian romantic medieval style with English-European Gothic and Romanesque decorative details. It has tall, segmentally-arched, mullioned, and transomed ground floor windows with stained glass in lower panes. Upper windows are trefoiled mullioned and transomed lights, and the central window cuts into a gabled dormer with a rose window, topped with a plain red tiled roof with ridge cresting. High-relief busts of artists and literary figures can be seen beneath the timber clerestory with overhanging eaves carried on paired timber shafts.

The ceiling to the staircase continues the romantic gothic style of the later Victorian period, inspired by medieval features. A hammer-beam roof decorated with elaborate plaster ribs steps up into the lower half of the steeply pitched roof.

Other early structural concrete buildings include St Mark's Church in Battersea, built between 1872 and 1874. This use of mass concrete was part of a broader trend of experimentation with new construction materials and techniques brought about by the Industrial Revolution. The church, designed by William White, occupies a triangular site on the corner of Boutflower Road. It was built with a concrete core, then faced with orange brick with red brick bands in a thirteenth-century style.

In the 19th century, mass concrete was increasingly popular in extensive infrastructure and building projects due to its strength and durability. For instance, The Albert Dock (completed in 1846) in Liverpool utilised mass concrete during its construction, contributing to its durability and functionality as a key maritime structure.

Oldham Library is one of only a few examples illustrating how mass concrete enabled the construction of robust and lasting structures during the 19th century, paving the way for widespread adoption in the 20th century and beyond. The walls incorporated mass no-fines concrete as a structural core material, which provided strength and bulk, especially useful in buildings that intended to project solidity and permanence.

At the time, using mass concrete was relatively innovative for church and public building construction, reflecting a growing confidence in the material’s capabilities to manage loads from the roof and upper parts of the building. Its use allowed for possibly faster construction times and introduced new possibilities in design and architecture compared to purely stone or brick structures. Mass concrete was favoured for its fire-resistant properties and ability to form into different shapes and structures, which was beneficial in constructing large, complex buildings like Oldham Public Library. The interior walls at the Library were covered with fine plaster finishes with curving chamfered details to openings, often terminating in a birds-beak detail.

M.Womersleys identified the areas of void filling on the face of the shuttered concrete walls and suggested how they might be repaired. The no-fines concrete should not be repaired with dense modern OPC-based concrete with much higher strength than the suspected 14 MPa of the old concrete. A mix of Coarse Sand and Natural Hydraulic Lime with 20% prompt natural cement was used to provide a suitable fill material. This mix, used in conjunction with bricks, low-fired clay tiles and limestone aggregate, was used to fill the deeper localised voids in the surface of the walls.

On a clean and dry background, after adequately damping down, the Roman stucco mix was applied while the previous layers were still damp, working “fresh on fresh”, i.e. waiting for the loss of workability, not the set. The rapid and controllable set, with low shrinkage risk and excellent bond strength, made it ideal for this wall structure.

The production process employed to make Prompt Natural Cement is virtually the same as that of lime. Prompt has many properties in common with the last century's natural cements. NHL is richer in hydrated calcium oxide (Ca(OH)2), while Prompt is richer in calcium aluminate and alite. The alite content is minimal in the case of Prompt, and Prompt's fast-setting and early hardening characteristics result from the hydration of the calcium aluminates. The small quantity of C3S is fully hydrated very rapidly, resulting in an additional increase in strength for up to 7 days. The slower hydration of the C2S ensures a continuous increase in strength over several months. The setting time for Prompt can be adjusted by adding specific retarders such as trisodium citrate and citric acid.

Prompt contributes to the sand and hydraulic lime mix by ensuring low shrinkage, satisfactory modulus of elasticity, moderate strength values, and rapid setting.

Related Articles

The steps members of the Waterton’s Wall restoration team, with support from Mark Womersley, have been following to consolidate, conserve and repair this historic wall that represents the successful efforts of Charles Waterton to preserve the wildlife that lived on his estate near Wakefield in West Yorkshire.

1. Fill deep voids behind the wall’s facing stones with deep pointing work. The works involve …

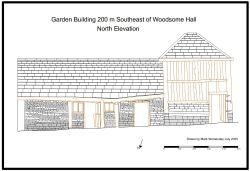

Mark spent a day recording a historic timber-framed garden building at Woodsome Hall

Mark Womersley, as part of his voluntary work with the Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group, spent…

M Womersleys were delighted to offer a day of tutoring to those who attended the Wentworth Woodhouse Working Party

M Womersleys were delighted to offer a day of tutoring to those who attended the Wentworth Woodhouse…