Investigations and treatment of salt contamination of the walls, behind and above-removed bookcases at Palace Green Library Durham

Introduction

Durham University was concerned about the salt-damaged plasterwork in this historic Exchequer Building. Following water penetration, some historical plasterwork had been damaged and de-bonded in some building areas. Some of the decayed plaster has been replaced with cement/lime renders, cement, and modern gypsum plasters, which had also been damaged and had exaggerated the salt damage.

After replastering with haired lime plaster, further efflorescence occurred following water leaks from the roof. The University asked M Womersley’s Ltd to undertake an additional survey of the localised salt-damaged stone on internal walls in the Palace Green Library after the historic bookcases were moved and to apply clay poultices to reduce the volume of salts nearer to the surface of the wall before replastering with lime-based plasters.

The history of Palace Green Library

In 1669, Bishop John Cosin founded an episcopal library on Palace Green, the first public lending library in the North East of England. In 1833, Durham University Library was established on the Palace Green site, with a foundation collection of 160 volumes donated by William van Mildert, the last Prince Bishop of Durham.

During the 1850s, Dr Martin Joseph Routh, Bishop Edward Maltby, and Dr Thomas Mastermann Winterbottom donated major collections to the Library. To house its growing collection, the Library was extended to occupy the upper two floors of the Exchequer Building, the former Bishoprick Law Courts on Palace Green, which dates from 1450. Today, the Exchequer Building is the only administrative building of the Prince-Bishops that has survived medieval times. This area required work by M Womersleys to reduce the salt contamination, especially on the internal stone walls at the first floor.

The fifteenth-century exchequer building.

The fifteenth-century exchequer building.

The procedures used to reduce salt contamination.

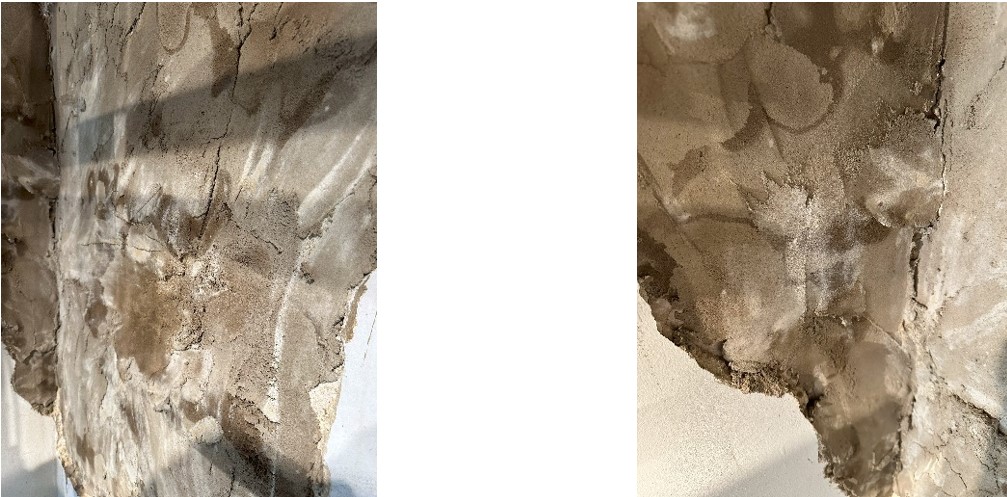

Building Surveyors within the Estates and Facilities Directorate of Durham University were concerned about the breakdown of the lime plaster that was applied seven years ago to the North and west walls of the North room of Martin Routh’s Library. Following continued water penetration, heavy salt contamination within the library walls transferred into the lime plasters, which began to break down. The University has asked M. Womersley’s Ltd to measure the salt contamination and apply clay poultices to draw it from the sandstone.

The area near the salt-contaminated stonework was cleared to ensure we could work comfortably. The library also protected the floor and nearby furniture with padded floor sheets, drop cloths, and plastic sheets. All the areas of exposed stone had visible salt deposits (often appearing as white powdery stains and crystals), and these were brushed off and vacuumed up, together with other loose materials, dust, and debris.

M Womersleys had prepared the wet clay poultice of rich grey clay and sand and began trowel-applying it to the walls, using small enough tools to work it into all the stone and mortar, including recessed areas. The poultice was applied as a thick, even layer (about 15 mm thick) to ensure it fully covered all the exposed stonework.

Because of the building's built-in humidity control, plastic wrap was unnecessary to prevent the poultice from drying too quickly. Helping maintain moisture enhances the poultice's absorption properties. The first coat of poultice was allowed to sit for one week before being removed from the walls and bagged up to take away from the site. The poultice was visibly rich in salts it had pulled out of the stonework.

The wall was brushed down, and all the residue was vacuumed up. M Womersleys then used semi-quantitative test strips to measure the residual sulphate salts. The salt concentration was halved with each poultice application, and three coats were applied and removed from the site over five weeks.

Using a clay poultice reduced the salt contamination in the stone and mortar joints in these older walls. Still, ongoing maintenance of the roof and drainage systems above is essential to prevent further water ingress and the transportation of new salts from deep within the wall to its internal surface.

Related Articles

On Sunday, March 16th, why not come for a full introduction to lime plastering and a practical demonstration workshop?

Learn more about traditional clay, lime, and ornamental gypsum plasters and their use internationally…

Proposals to carry out a conservation assessment at Wukro Cherkos, with a full training programme for recent graduates from Mekelle University and government bodies responsible for regional conservation work.

Introduction In response to continued concerns about the condition of one of Tigray’s most well…

Report on the support given by M Womersleys to Jabir Mohamed at Berbera Museum, Berbera, Somaliland, over two weeks from the end of October 2024

Contents …